It's Like Riding a Bike: A Classroom Culture of Personal Connections

If you are in the market for a new home, you know the process can be quite overwhelming. For 7th graders in Michelle Gross’s math class in Spencer County, that process will be much less intimidating when the time comes. From appraisals to mortgage payments, they know how it works. All result of a single driving question, “How can I use proportional reasoning in the real world?”

To answer that question, these ambitious 7th graders designed their dream homes. They mastered calculating square footage, conducted research on floor plans, and drew a scale model with their own personalizations to the existing blueprints using the tools of architects. Additionally, they calculated what a reasonable home price would be by averaging three similar homes in the area, calculated the mortgage payments with and without down payments, and ultimately calculated a yearly income they’d need to afford that home. Finally, they shared their plans with professional architects and contractors, peers, teachers, and younger students [check out presentation day here].

Gross’s students know more about the home-buying and building processes than many adults! Of course, this wasn’t a class in architecture, design, or finance. It was a 7th grade math class studying ratio and proportional relationships- the same content many of us probably learned comparing obscure baskets of fruits. While our worksheets likely went swiftly into the trash, Olivia, one of Gross’s 7th graders, says she won’t be throwing her Dream House Project away, “I’ll look back at it for future reference.” Her classmate, Bella, agrees, “I’ll definitely use it [my project] in the future like for building my own house.” It was obvious these students deeply understood the content and are proud of their work.

This project is just one example oStudents share that learning in her class is “hands-on and fun” and “relates to stuff you do.” On a daily basis, from large scale projects to flashback routines, Gross creates a community of mathematical thinkers invested in solving relevant, rigorous problems.

How Gross is transforming the student experience

In Gross’s class, you won’t see pages and pages of problems unrelated to students' lives in any way, but instead an in-depth, collaborative analysis and application of mathematical concepts using relevant, personal examples for each student.

“I don't want them to see math in isolation,” says Gross. “When kids are thinking about math in relation to things they care about, engagement is higher.”

When teaching about the relationship between circumference and diameter, Gross begins with the prompt, “Describe your first bike.” Students recall and find pictures. They show each other and laugh. Gross shows an ad for a child’s Spiderman bike, “What’s the size of that bike’s wheel?”

A student responds, “16 inches.”

Gross, “What’s that referring to?”

Another student, “The circumference?”

Gross, “Would that make sense?”

Student, “No, that’s too small. Maybe the diameter?”

Gross, “That’s it!”

Students then research their dream bicycle identifying the diameter of their respective wheels. Some show pictures of mountain bikes, others speedsters, and even a unicycle. She asks kids which of those bikes they would select to ride from one end of a football field to the other. How many revolutions would it take on that bike? Students work together to come up with an answer, then discussed, whole-group, the strategies they used until all students had a conceptual understanding of the relationship between circumference and diameter.

Gross designed the lesson in hopes of making the math relevant, “If I just taught the lesson and had them do practice problems, as long as they had that formula, they would be able to answer questions in isolation. We would move on. They wouldn’t think about it again. But my hope is that when that circle comes back up, they immediately picture bicycles in their mind. If they have to look at a formula, that’s okay- that’s what we have Google for. But that connection and conceptual understanding is there and it sticks with them.”

Learning that is relevant sticks. Gross’s students can attest to this. After sharing photos of the Dream House project on Facebook, students from years ago responded remembering fondly when they did the project in her class. Furthermore, parents notice the difference. Gross shares, “I had posted it on our seventh grade support page and our parents were like, ‘oh, my kid came home and they were talking about it. And I love seeing their creativity!’”

Gross’s students echoed this excitement about learning math in her class. Kimberly, one of Gross’s students, shares, “In here, it’s hands- on, fun learning that relates to stuff you do. We go deeper in explanation and understand WHY.”

Another student, Nate, adds, “We also have freedom, like in our Dream House Project, it wasn’t just a set of questions. You couldn’t really get it wrong because it’s yours! We got to learn about others and see what they were doing.”

A third student, Cali, agrees, “Yes, we got to help each other and keep revising our work.”

Time for feedback and revision are essential in Gross’s classroom, “I think people need time to think. I try to give them time to think about it themselves. Then time to talk to each other about it.”

That time makes all the difference for students like Olivia who says, “I always feel rushed. I always feel like I need more time, and Ms. Gross gives us that time. In my Dream House Project, I got feedback and learned from my mistakes on my blueprints. I actually revised it to make an extra closet.”

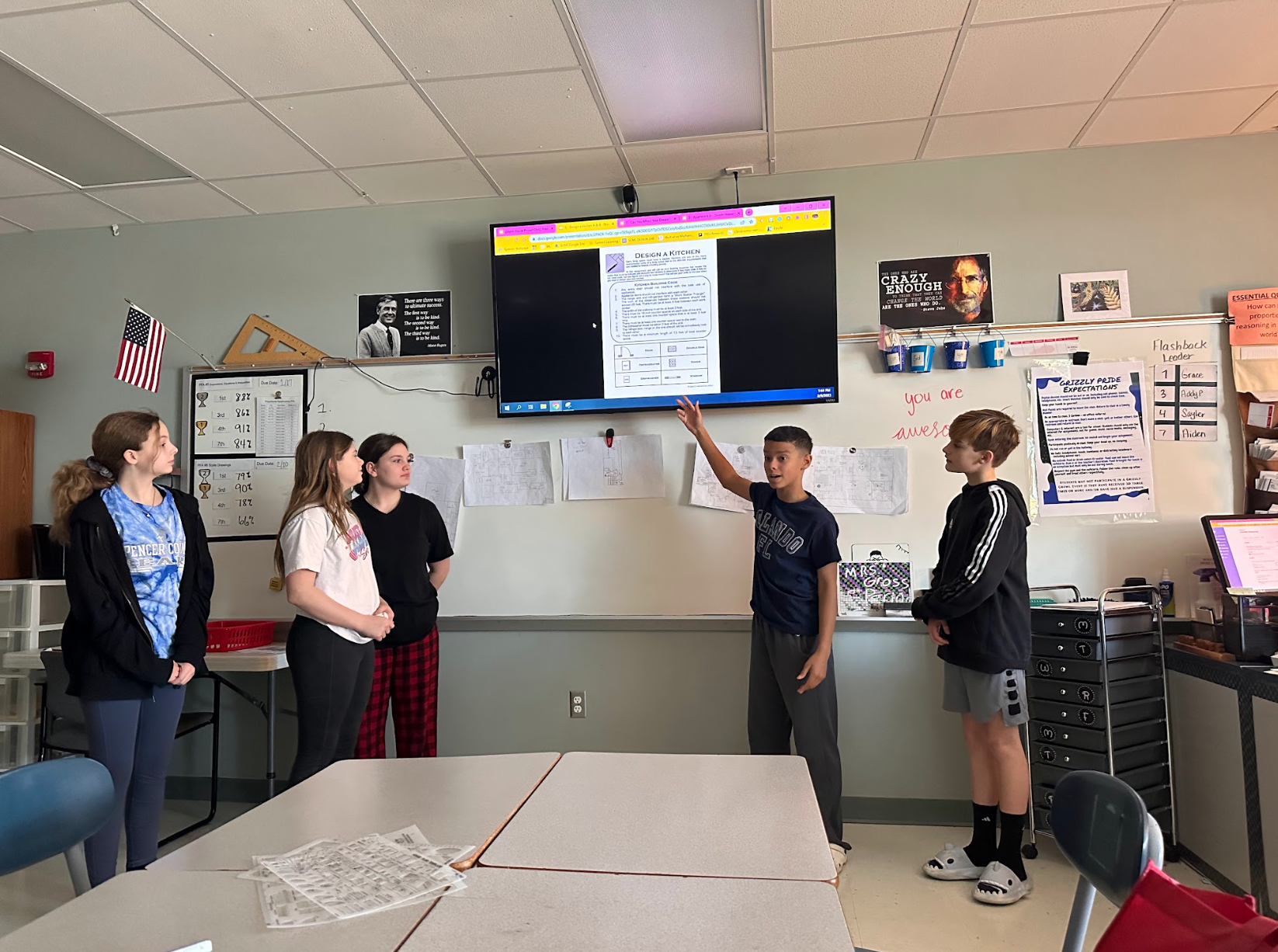

Collaboration and revision are the norm in Gross’s class, not a ritual reserved for larger projects. Daily, her class engages in a student-led flashback routine. The class is posed a series of questions revisiting content. Students work in their table groups to collectively solve each problem, asking each other clarifying questions and thinking through strategies together. Each day a different student leads a whole class reflection on the questions. When the whole class has consensus on an answer, they move onto the next question.

When the class disagrees, the student leader guides the class through a reflective process to reach consensus. Ms. Gross observes the process, only interjecting to encourage a hesitant student’s thinking. Throughout the routine, students have the opportunity to revise their answers. This emphasizes the process, the student collaboration and feedback, is what’s important, not the answer in and of itself.

That on-going reflection, grounded in work students deeply care about, pays continuous dividends. Gross shares, “The other day when we were preparing for the presentations, one of the girls was like, ‘wow, I'm learning so much. I did this work and I'm still learning so much.’”

How to get started

Gross acknowledges that finding relevant connections might seem overwhelming. Her advice? “It could be as simple as looking at a textbook question and finding the question in there that you're like, I can connect to the kids with this question.” Hence the bicycle lesson.

“When I first started teaching geometry, I was a little intimidated by teaching it because it was my least comfortable thing to do in school. So I knew I needed some real world applications,” Gross shares.

That was the genesis for her Dream House Project. “Scale was one of those things that kind of bridged the gap between proportional thinking and geometry. I had seen some people do the Tiny Home Project, and I know that for years and years, math teachers have had kids do blueprints because it's the most real world thing. So that's where I started. And it was very, very basic. It was really just like, let's start drawing.”

That project continually evolved, becoming more relevant and rigorous with each iteration. The real shift for her came when she started thinking of the project “as the umbrella.”

“A lot of people teach the lessons, do the activities, take the test, and then have the project- they tack it on. There’s just not enough time. So I shifted my focus to the project- I saw it as my umbrella- the Dream House was a vehicle for students to reproduce scale. Each piece to get there is like a spoke on the umbrella.”

Students echo this emphasis on the importance of projects as a vehicle for learning. Cali’s advice for weighing how to ‘fit projects in’: “Do the project instead of the worksheet. We need to do these projects because we will learn what we need to in ways we care about.”

Lastly, Gross shares that it's okay to borrow from others, “If creating something completely new is intimidating, start with something that someone has already created and make it your own. That’s exactly how the Dream House Project started.”

Simple Shift Call-Outs

- Provide Structure for collaboration, feedback, and revision Gross's flashback routine and Dream House project gave students protocols for engaging in collaborative, continuous learning.

- Make it personally relevant Look for opportunities, even as small as the bicycle questions, to connect learning to students' lives.

- Make thinking visible Create spaces and time, such as sharing blueprint designs or collaborative problem solving structures, for students to learn from each other's thinking.